What has the UK to gain from participation in the North Sea alliance?

Unlocking integrated solutions

On 18 December 2022, the UK entered into a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the North Seas Energy Cooperation (NSEC) which “sets the framework for greater cooperation with North Seas neighbours … on development of offshore renewable energy and grid infrastructure essential for meeting UK net zero commitment and bolstering European energy security”.[1] This follows through on one of the few energy interventions from the short-lived Truss government.

Subsequently, on 24 April 2023 at a North Sea Summit, the UK announced further bilateral agreements including agreement in principle on the LionLink project with the Netherlands. This is a hybrid 1.8GW interconnector and associated offshore windfarm.

What is NSEC?

NSEC is a cooperation between 9 countries (Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden) and the European Commission, intended to support the development of offshore renewable energy. It was established in 2016, building on the prior North Seas Countries’ Offshore Grid Initiative (NSCOGI) which was set up in 2010. Both the NSEC and NSCOGI included the UK prior to Brexit. While Norway is outside the EU, it is – unlike the UK now – fully integrated into the internal electricity market.

The new form of cooperation under the 2022 MOU is broadly equivalent to observer status rather than full membership. It provides for UK government representatives to be invited to attend for agenda items of common interest and for annual meetings to review progress jointly. This is a fairly normal approach for the involvement of third countries in EU bodies but could mean initial progress on collaboration is slow as relationships need to build through ad hoc invitations rather than full membership.

How do other countries’ North Sea offshore wind targets compare to the UK?

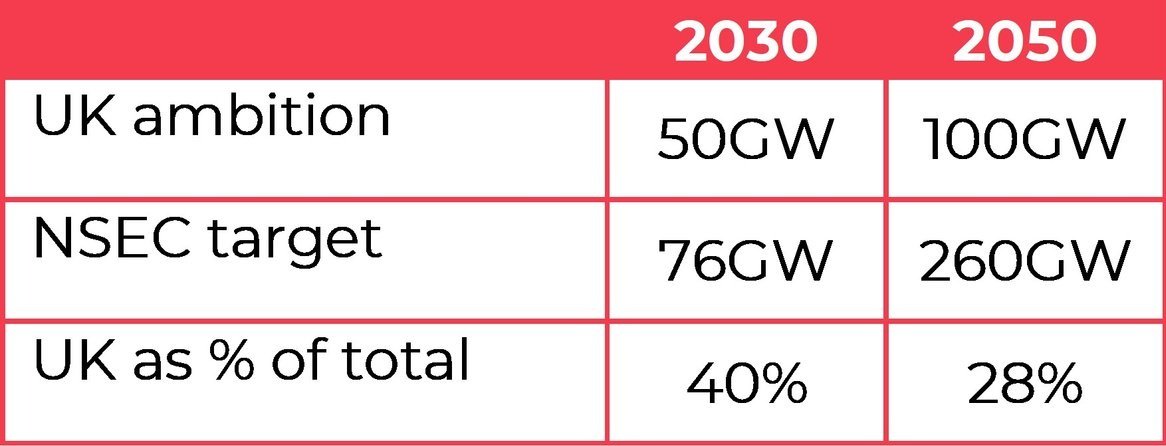

The UK government’s targets for offshore wind by 2030 have grown over time to a current “ambition” of 50GW, which is unlikely to be met given current rates of deployment. In the longer term, the UK net zero pathway is expected to involve about 100GW by 2050.

The NSEC countries have agreed on targets which collectively imply 260GW by 2050, with intermediate targets of 76GW by 2030 and 193GW by 2040.

The UK target looks particularly ambitious in the near term, amounting to 40% of the combined UK+NSEC capacity by 2030. However, the NSEC targets then imply stronger growth over the following decades, so that the UK drops back to 25-30% of the total by 2050.

Table 1 – Comparison of offshore wind capacity targets

Some of the NSEC countries are already looking at “energy islands” or hubs, beyond the radial connection model – Belgium being an early mover, with plans for a coordinated Dogger Bank hub involving Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands.

Is cooperation needed?

In the development of offshore wind to date, each country has largely been able to proceed separately. But as we see in the UK, future developments increasingly require more coordination in planning and grid infrastructure, if they are to be completed efficiently and avoid excessive disruption to coastal communities where the power comes ashore.

With the volumes envisaged by 2030 and beyond, in the parts of the UK closer to our neighbours, the most efficient approaches to grid development may increasingly involve the integration of offshore wind connections and subsea interconnectors – so-called hybrid projects – or even a more meshed subsea grid, which brings additional technical issues. These considerations give rise to questions of how the infrastructure will be funded between the countries involved and regulated, and how the offshore windfarms will be integrated into markets – issues which can only be resolved collaboratively.

Alongside the revenue and investment models for the windfarms and transmission assets, both the UK and NSEC countries have strong interests in the supply chains to develop, construct and operate these assets. Whilst these interests may be in tension to some degree, it seems more likely that the overriding issue will be building sufficient capability to deliver on the ambitious targets and so joint planning and information sharing could have real value.

NSEC and the UK are beginning to develop regulatory models, but failure to address broader mismatches could undermine investment

As noted above, the NSEC countries are already developing models for offshore hubs and energy islands. In the UK, Ofgem has been developing a regulatory framework for multi-purpose interconnectors, launching two consultations at the start of June,[1] one jointly with DESNZ. This builds on decisions earlier this year to take forward two hybrid projects, to Belgium and the Netherlands respectively, as pilots, with a further two to Norway on hold.

In most markets, a producer with options to sell into either of two markets will look to sell to the one that values its product the most – the one willing to pay the higher price. The Ofgem/DESNZ consultation proposes that an offshore windfarm connected to two markets will be paid the lower of the two prices, through the offshore bidding zone (OBZ) model. Having shrunk revenues, it then proposes to increase them through a subsidy paid by consumers in one of the markets. The windfarm will also be exempt from onshore transmission charges, reducing locational signals and increasing the divergence of its competitive position from a windfarm connected solely to the GB market.

Further complications arise in regulation of the transmission assets, not least in terms of how they are categorised, with a flurry of new acronyms proposed.

There is a logic to these proposals, in terms of alignment with aspects of the EU regulatory regime applicable to our NSEC neighbours. But the Ofgem consultations rather give the impression of ploughing into the complicated technical detail, without stepping back to see the bigger picture and understanding the distortions to investment choices these models could create through their interaction with broader aspects of the GB model that differ from those in our NSEC partners.

The OBZ model has an advantage in being a natural extension of the main market model across the EU based on price coupling between geographical markets, particularly if the OBZs are based on hubs or islands rather than individual windfarms. However, post-Brexit, the GB market is now outside of the price-coupling model and has chosen to decouple further by splitting the two day-ahead exchange prices, so is a long way from compatibility with the NSEC model.

For the OBZ model to work efficiently, the GB market would need to be reintegrated into the EU market and the relevant GB price would need to be an efficient signal. With the ongoing constraints in the GB system, this arguably means the GB price would need to be zonal or nodal, as being explored in the Government’s Review of Electricity Market Arrangements (REMA). But nodal prices are arguably inconsistent with the EU model.

The GB and NSEC approaches to planning are also quite different, as we explored in our last blog[2]. The NSEC markets tend to pre-determine the locations of offshore windfarms, so do not depend on efficient price signals to influence the siting of generation. The GB approach is more open to a choice of location, so the absence of efficient signals such as zonal or nodal pricing, matters more.

At present, from a GB perspective, the approach to grid infrastructure still feels somewhat incremental. A broader, North-Sea-wide review of the most efficient technical solutions for grid infrastructure, perhaps back-casting from 2040 or 2050 scenarios, may help. This could be delivered through the Electricity System Operator (ESO) working with Its European counterparts (ENTSO-E)[3] although it would be important to ensure sufficient new thinking and flexibility is built in the assessment – routine turning of the handle on existing models will likely miss opportunities.

With their focus on technical regulatory complexities, the Ofgem consultations do not draw out these broader challenges. In fairness, the consultations recognise that there is considerable further work needed. But…

Time is running out to get investable frameworks in place

Given the time taken to develop and construct projects, the initial targets for 2030 are now pressing, and we are missing the boat for hybrid or meshed grid solutions to help. With the UK offshore wind targets front-loaded compared to our neighbours, we risk locking into less efficient solutions. Urgent focus is needed on solutions and there is no time to be lost in delving down rabbit holes.

Ten years ago, the UK put significant effort into the first iteration of this collaborative approach through NSCOGI. Interest waned with concerns that NSCOGI would not deliver near-term practical solutions. While energy policy makers are currently focused on multiple other challenges, such as the ongoing pressures of high retail prices, real integrated North Seas projects are now in sight, and urgent, well-directed and effective collaboration is needed if the policy framework is not to hold them back.

Past experience shows that real change is possible in European energy rules with smart and persistent engagement. DESNZ and Ofgem will likely need support from interested industry participants if they are to achieve this.

The MOU and subsequent consultations are therefore very welcome but need to be backed by clear direction and determined efforts to establish an effective, workable and above all, investable, model.

Ultimately the success of collaboration under the MOU still hinges on broader cooperation between the UK and EU – indeed the MOU itself expires in 2026 unless continued as part of broader cooperation through the Trade and Cooperation Agreement. But if we want to make the best of the huge opportunity of offshore renewables and maximise its contribution to net zero, we really must use that window as productively as possible.

[1] DESNZ press release, 18 December 2022

[2] Consultation on the Regulatory Framework, including Market Arrangements, for Offshore Hybrid Assets: Multi-Purpose Interconnectors and Non-Standard Interconnectors | Ofgem closing date 14 July 2023

[3] Offshore wind auction processes from Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands — Complete Strategy (complete-strategy.com)

[4] European association for the cooperation of transmission system operators